There has been a lot of discussion recently on the stance of monetary policy. As noted over at Macroblog, many observers believe that monetary policy has been too loose as evidenced by the negative real (or inflation-expectations adjusted) federal funds rate. These observers are concerned that a negative real policy rate may cause, all else equal, inflationary expectations to become unanchored and lead to a repeat of the 1970s-like inflationary spiral. Some

observers argue, though, that all else is not equal and that negative real interest rates do not necessarily imply these outcomes. Rather, one must look at real fed funds rate relative to its neutral rate value.

Paul McCulley of

PIMCO puts it this way:

All sensible discussion of the “right” real Fed funds rate logically must begin with the proposition that the putative “neutral” equilibrium real Fed funds rate is not constant, but rather time varying, a function of financial conditions, notably whether levered financial intermediaries – conventional banks, as well as shadow banks, a term I coined last year at Jackson Hole – are ramping up or ramping down their leverage. The former will lift the “neutral” real rate while the latter will reduce it. Thus, a high Fed funds rate may not be restrictive at all while a low Fed funds rate might not be stimulative at all.

I too agree one should look at the neutral rate value when assessing what the fed funds rate tells us about the stance of monetary policy. However, I would go beyond just financial conditions as suggested by

McCulley and also consider productivity growth,

intertemporal preferences, and population growth--the determinants of the natural interest rate in a standard growth model-- in assessing the neutral interest rate. Doing so, however, is non-trivial task and many

sophisticated econometric attempts have been made with mixed results to estimate the neutral rate.

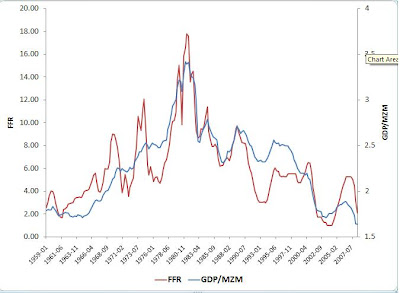

One easy way to get a sense of whether the fed funds rate is near its neutral rate is to use what I call the policy rate gap measure: the difference between the year-on-year nominal growth rate of the economy and the federal funds rate. This measure, popular with

The Economist magazine and some industry

economists, shows monetary policy to be too loose when the federal funds rate is significantly below the economy's nominal growth rate and too tight when it is significantly above it. According to

Brian Wesbury, the federal funds rate should be within 1% of the economy's nominal growth rate to be neutral. This measure is convenient because it provides an approximation to a neutral fed funds rate without having to resort to real values. [Both measures are in nominal terms so the inflation component drops out in the differencing.]

I have been highly interested in this measure and have

shown previously that it does a good job predicting recessions. One issue that has recently come to my attention, though, is how to best measure the economy's nominal growth rate. Previously, I used nominal GDP in constructing this measure. However, some

commentators have pointed to Gross Domestic Income as a better measure of current economic activity. Jeremy

Nalewaik, in particular, has

shown that “real-time

GDI has done a substantially better job recognizing the start of the last several recessions than has real-time GDP.” With these findings in mind I constructed the policy rate gap measure with both GDP and

GDI to get a sense of the stance of monetary policy today. Here is what I got (click on to enlarge):

These figure indicates that if

GDI is used, monetary policy is indeed neutral as suggested by Paul

McCulley. If, however, GDP is used then there is a stronger case that monetary policy has been loose. Currently I am inclined to cast my lot with

GDI--the bad economic

news today seems to confirm my prior--and conclude monetary policy is more or less neutral. For good measure, I also made note in the graph of the massive Greenspan monetary easing of 2003-2005.

Update: Although it may be clear to some readers, the above post does not explain why the policy rate gap can be considered a measure of the stance of monetary

policy. To correct this omission, I turn to

The Economist magazine who says the the way to “interpret this [measure] is to see America’s nominal GDP growth as a proxy for the average return on American Inc. If the return is higher than the cost of borrowing[i.e. the interest rate], investment and growth will expand [and vice

versa]. Alternatively, one could argue if the real economy is growing faster as the result of productivity gains or population growth (via increased labor supply, which in turn implies a higher marginal product of capital,

ceteris paribus) and assuming

intertemporal preferences are relatively stable, then the real interest rate should be higher too. Throw in the nominal component to the measures of the real economy and real interest rate and one should see similar movements and/or convergence in the nominal growth rate of the economy and the federal funds rate. If these patterns are absent, then one can argue that monetary policy is causing the real rate to deviate from the rate implied by the fundamentals.