Pages

Saturday, February 28, 2009

More on the Eastern European Economic Crisis

Friday, February 27, 2009

Another Look at the Collapse of U.S. Domestic Demand

This means nominal spending is crashing in the United States. Addressing this collapse should be one of the top--if not the top--objectives of macroeconomic policy as recently noted by Scott Sumner, Samuel Brittan, and Martin Wolf. Such a large drop in domestic demand means either (1) a collapse in real spending and thus real economic activity and/or (2) deflation. Obviously the former is not good news, but the latter is also bad news since it can set off a deflationary spiral that leads to further real declines.

Another Unexpected Outcome of this Recession: More Art

Tough times can often be a springboard for creativity; when no one's job is safe, no one's house is secure and no one knows exactly what to do about it, artists get to work.I am looking forward to this development.

"That kind of stress often results [in] the need to scream, and art is a way of screaming," says Miles Orvell, an English and American studies professor at Temple University. "Difficult times like the one we are experiencing today can really bring out a kind of expressive culture in an interesting way."

The Future of the Euro (Part VI)

Feb. 27 (Bloomberg) -- Hayman Advisors LP, the firm that earned $500 million betting on the U.S. subprime mortgage-market collapse, says Europe’s monetary union is about to fall apart.So a "growing number of investors" are seeing a greater likelihood of the Eurozone breaking up. If so, you would think these investors would be adjusting their portfolios accordingly. There is an intrade contract that indicates the probability of a nation dropping its use of the Euro by December 31, 2010 has not change much since July 2008 (see figure below). This contract suggests that a "growing number of investors" may be a bit of an overstatement. Or maybe this contract is to thinly traded to truly reflect the increased fear about the Eurozone. Any thoughts?Richard Howard, a managing director for global markets at Dallas-based Hayman, said Germany may opt to shore up its own economy, Europe’s biggest, rather than bail out fellow euro nations such as Austria, Italy and Spain as their banks sag under the weight of bad debts. That might lead to defaults and compel Germany to renounce the euro, he said.

“People said subprime could never blow up but it did and now they’re saying the exact same thing about the eurozone,” said Howard. “There’s no stopping what is now a downward spiral.” He declined to discuss his investments.Hayman joins a growing number of investors seeing the possibility of a breakup of the $12 trillion euro bloc, conceived more than 10 years ago to cut unemployment, tame inflation and create a rival to the dollar. Societe Generale SA said this week Germany may refuse a bailout in an election year. ABN Amro Holding NV said Feb. 17 the crisis is “Europe’s subprime.”

[...]

The breakup may occur as investors shun all but the safest government bonds, said Hayman, which in 2006 was among the first to bet against Wall Street’s rush to securitize the debt of the least creditworthy U.S. borrowers, correctly predicting a slump in home values that sparked the global credit crisis.

Investor demand for the lowest-risk securities already drove the difference in yield, or spread, between Greek, Austrian and Spanish 10-year bonds and German bunds, Europe’s benchmark government securities, to the widest since the euro’s debut.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Clive Crook on Long-Term U.S. Fiscal Costs

This year’s budget deficit will be about $1,400bn (€1,090bn, £977bn) or roughly 10 per cent of gross domestic product. This comprises $1,200bn, as recently estimated by the independent Congressional Budget Office, plus another $200bn from the first year of the fiscal stimulus. What happens after that? A new analysis for the Brookings Institution by Alan Auerbach and William Gale estimates that the deficit will average at least $1,000bn a year over the next decade – and this on the basis of some pretty optimistic assumptions.

It assumes an orderly recovery, much as from previous recessions: no lost decade of slow growth. It assumes that the provisions in the stimulus law expire when the act says, even though the administration and Congress hope to make many of them permanent. It takes no account of new outlays under the housing plan or the forthcoming financial stability plan. And it assumes the administration does not embark on comprehensive healthcare reform, even though the White House insists it will.

Even under these favourable assumptions, an annual deficit of $1,000bn or more persists. The Auerbach-Gale study also looks further ahead and estimates a “long-term fiscal gap” – “the immediate and permanent increase in taxes” that would be needed to keep the ratio of government debt to GDP constant at its current level. Under those same favourable assumptions, the necessary tax increase is between 7 per cent and 9 per cent of GDP, about equal to the take of the present federal income tax.

Stephen Colbert on Religion & the Business Cycle

Saturday, February 21, 2009

About That Economic Downturn of 1873...

The figure below shows the log version of these three series for the Postbellum period. Nowhere in this figure is there 5 year + economic downturn in the 1870s. (Click on figure to enlarge.)

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Inspirational Morning Reading

It is now clear that this is the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression and the worst economic crisis in the last 60 years. While we are already in a severe and protracted U-shaped recession (as the deluded hope of a short and shallow V-shaped contraction has now evaporated) there is now a rising risk that this crisis will turn into an uglier multi-year L-shaped Japanese style stag-deflation (a deadly combination of stagnation, recession and deflation). The latest data on Q4 2008 GDP growth (at an annual rate) around the world are even worse than the first estimate for the US (-3.8%): -6.0% for the Eurozone; -8% for Germany; -12% for Japan; -16% for Singapore; -20% for Korea. The global economy is now literally in free fall as the contraction of consumption, capital spending, residential investment, production, employment, exports and imports is accelerating rather than decelerating.Now I am inspired.

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

The Beginnings of a Fiscal Transfer Mechanism for the Euro Area?

Here is the story:

Germany, France May Face Bailout of Euro Nations Feb. 18 (Bloomberg) -- Germany and France may be forced to contemplate the bailout of entire nations rather than just individual banks as European government budgets buckle under the weight of recession.

German Finance Minister Peer Steinbrueck became the first senior policy maker to broach the topic earlier this week, saying some of the 16 euro nations are “getting into difficulties” and may need help. He went further today, saying Germany would show its “ability to act.” French officials are also concerned about market tensions as the cost of insuring Irish, Greek and Spanish debt against default rises to records and bond spreads widen.

The nightmare for Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy is that widening deficits will prompt investors to shun the debt of some countries, sparking a region-wide crisis. While few investors are yet forecasting any defaults, the mere risk of it may prompt the bloc’s two richest economies to ignore the European Central Bank and announce their willingness to come to the rescue.

[...]

Part of the problem policy makers now face stems from the fact the currency union does not have a single treasury and relies on the Stability and Growth Pact, which has been breached in the past, to keep budgets in check. Billionaire investor George Soros said yesterday the region’s economy must confront the problem posed by the lack of a Europe-wide finance ministry.

Here is Bloomberg TV on the story:

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Martin Wolf On What Needs To Be Done

(1) Keep financial markets working.

(2) Stabilize domestic demand.

(3) Deal with the insolvent banks and households.

I think these are spot-on prescriptions for economic recovery. Observers may argue about the specifics of these points, but in my view they address the key problems. Yes, there is nothing new here and some of the points are already being addressed, but I have not seen anyone pull these issues together so nicely in one discussion. Click on the picture for the video clip.

Friday, February 13, 2009

Some Interesting Reading

1. The credit crunch in a flow chart--Barry Ritholtz

2. The world economy looks scary--Rebecca Wilder

3. A truly global slump--Brad Sester

4. Moody downgrades USA credit standing--Felix Salmon

5. Photo essay on global financial crisis--Foreign Policy

6. Unnecessary Depression Angst--Morgan Stanley Global Economic Forum

7. No golden fetters this time around--Nick Rowe

More on What the Fed Can Do to End This Crisis

Ben Bernanke should publicly bet $1 trillion dollars that the US economy will recover quickly from deflation and recession. He should make that bet on the Fed's behalf. The Treasury should publicly disavow all responsibility for bailing out the Fed if Bernanke loses the bet. If he loses the bet, it would be paid for by printing money.There is more to Nick's strategy in his post, but the key point is that it would change the public's deflationary expectations. This ability to change expectations is something the Fed still can do to help end this economic crisis.

This is how people would react to the bet.

If they expect deflation and recession to continue, so they expect Bernanke to lose the bet, they will expect the Fed to print an extra $1 trillion, which would be highly inflationary.....which is a contradiction.

If they expect the economy to recover quickly, so they expect Bernanke to win the bet, they expect the Fed will not print an extra $1 trillion, so they will not expect hyperinflation, just a normal recovery, which confirms their expectation.

By making such a bet, and making it publicly, the Fed creates the very expectations it wants to create: that deflation and recession will not continue, and that the economy will recover, and return to the normal rate of inflation.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Is the Chinese Yuan Significantly Undervalued?

China has been accused of “manipulating” its currency by Tim Geithner, America’s new treasury secretary, and this week Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the managing director of the IMF, said that it was “common knowledge” that the yuan was undervalued. You would assume that such strong claims were backed by solid proof, but the evidence is, in fact, mixed.Meanwhile, Foreign Policy says that this whole discussion is moot since China's currency "manipulation" does not matter.

Is U.S. Monetary Policy Really Tapped Out?

...We need a big fiscal boost program because monetary policy is already tapped out--Treasury interest rates are at zero--and employment losses are about to be bigger than in any previous recession since the Great Depression.Other observers go on to say that even unconventional U.S. monetary policy, such as the Fed's quantitative easing, has its limits. Representing this view is Paul Krugman:

Yes, there are other things the Fed could do — and it’s doing them, on an awesome scale. But they’re controversial, precisely because, unlike conventional monetary policy, they involve picking and choosing among potentially risky investments. And there’s a much stronger case for fiscal policy than in normal times, because we don’t know how well these unconventional measures will work.So conventional monetary policy is not working and the efficacy of unconventional monetary policy is uncertain. Maybe so, but I have a few questions. First, how do we know that unconventional monetary policy is not working? On the credit crunch front there is evidence that the Fed's policies are working to some degree as pointed out at macroblog. Also, monetary policy's effect on the real economy typically occurs with a lag so it seems premature to pass judgment here. Second, are we even sure that unconventional monetary policy is being fully exploited? I say this because of the Fed's policy of paying interest on excess reserves. This policy seems highly counterproductive given the state of the economy. What would happen if the Fed dropped this policy and did not attempt to sterilize these reserves? I suspect we would not see pictures like this one (click on figure to enlarge):

For those who are concerned that such a move would let the inflation genie out of the bottle I would (1) point you to this troubling figure that suggests deflation is more of a threat and (2) ask you to read Nick Rowe's discussions here and here. It is possible that banks would continue to hang on to the excess reserves in the absence of this policy, but given the improvements in credit markets it seems that at least some of these excess reserves would be put to good use. So I ask again is U.S. monetary policy really tapped out?

Update: See JKH's discussion in the comments section. Among other things, he explains that contrary to my assertion above the Fed's policy of paying interest on excess reserves is not consequential to the current excess reserve buildup.

Dr. Doom: Macroeconomic Policy Is Limited

First, monetary policy – however aggressive – is like pushing on a string when you have a glut of capacity and credit/insolvency rather than just illiquidity problems. Second, fiscal policy has its limits in a worlds where you are already the biggest net debtor and net borrower in the world and where you need to borrow this year $2 trillion net ($2.5 trillion gross) to finance your fiscal deficit while every other country (including your traditional lenders/creditors) are now running large fiscal deficits with the risk of a sharp back-up in long-term interest rates once the tsunami of new US Treasuries hits the market (see the back-up in Treas yields in the last 10 days and the scary signal it sends about coming dislocations in the US Treasuries market). Third, the US is taking an approach to bank recap and clean-up that looks more like Japan (convoy system and delayed true clean-up as the necessary pain to shareholders and unsecured creditors of banks is avoided/delayed) than the successful Swedish outright takeover/nationalization process. Fourth, the market friendly approach case-by-case approach to the necessary debt reduction of insolvent private non-financial agents (corporate for Japan, households for the US) will be too slow as working out one household at the time the debt overhang of 15 million insolvent households will take years when a systemic debt overhang requires an across the board debt reduction (as in Mexico and Argentina) that is not politically feasible – so far – in the US.No wonder he is called Dr. Doom.

Thus, even if the US were to do everything right and fast enough (on the monetary, fiscal, bank cleanup and household debt reduction) we would still have a severe two year U-shaped recession until early 2010 with a weak recovery of growth (1% or so that feels like a recession even if you are technically out of it) in 2010-2011. But if the US does not do it right this severe U-shaped US and global recession may turn into a nasty multi-year L-shaped near depression like the one experienced by Japan. We don’t have to go back to the Great Depression (when output fell over 20% and unemployment peaked over 25%); even a stag-deflation and Near-Depression like the Japanese one would be most severe for the US and the global economy. And while six months ago I was putting the odds of this L-shaped near-depression at 10% or so such odds have now risen to one third...

Monday, February 9, 2009

No, Greenspan Was Not Right

In 2003, Alan Greenspan argued that the Fed needed to set low interest rates to prevent falling into a liquidity trap and deflationary spiral... In 2008, Greenspan's critics argue that those same low interest rates caused an asset bubble, which burst, causing the economy to fall into a liquidity trap and deflationary spiral. Is it possible that Greenspan and his critics were both right? Was the US economy doomed either way?My answer is no. A deflationary spiral of the kind Nick describes is the result of a collapse in aggregate demand that creates expectations of further declines in nominal spending and ultimately the price level. Along the way the policy interest rate hits its lower bound of zero, real debt burdens increase, and financial intermediation gets disrupted. These conditions better describes today than 2003. The deflation scare of that time was simply a panicked misreading of deflationary pressures arising from robust productivity gains. To make my case I have re-posted with some editing portions of a previous post:

These next three figures make my case. The first figure shows productivity--as measured by non-farm business labor productivity--did see an acceleration in its year-on-year (Y/Y) growth rate around 2003:So Greenspan may have thought a deflationary spiral was around the corner in 2003, but the data indicates there was none in sight.

The figure also shows the ex-post real federal funds rate (ffr) relative to the Y/Y productivity growth rate. Assuming there were no significant changes in intertemporal preferences and population growth rates, this first figure suggests the Fed was pushing its policy rate down as the natural rate--which is a function of intertemporal preferences, population growth rate, and productivity growth rate--was increasing.

The next figure shows the Y/Y growth rate of nominal spending--measured by final nominal sales to domestic purchasers--against the nominal ffr. The year in question, 2003, is highlighted by the two dashed lines. This figure indicates nominal spending or aggregate demand was not collapsing but rather growing throughout 2003. The ffr, on the other hand was being pushed to down to 1%.

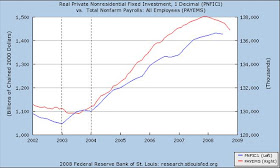

So productivity was increasing and aggregate demand was not collapsing. What about the weak labor market? One story is that the "jobless recovery" was simply the consequence of the above productivity gains. Another story is that the existing low ffr was pushing the cost of capital down and encouraging an inordinate substitution of capital for labor by 2003. In either case, there is no justification for further lowering of the ffr in 2003. The figure below sheds some light on this view. It graphs real non-residential fixed investment against total nonfarm employment with the year 2003 again delineated.This figure shows that non-residential fixed investment was recovering in 2003 while employment remained flat. Firms, therefore, were investing in their capital stock while avoiding new additions to labor. I suspect monetary policy played some role in this development.

Friday, February 6, 2009

Industries Losing the Most Jobs

Monday, February 2, 2009

The Latest State Employment Numbers

By way of comparison, here is employment in California and Florida:

By way of comparison, here is employment in California and Florida:

Below is a table for employment changes over 2008 for all states:

Below is a table for employment changes over 2008 for all states:

The Latest Installment in the New Deal Debate

The goal of the New Deal was to get Americans back to work. But the New Deal didn't restore employment. In fact, there was even less work on average during the New Deal than before FDR took office. Total hours worked per adult, including government employees, were 18% below their 1929 level between 1930-32, but were 23% lower on average during the New Deal (1933-39). Private hours worked were even lower after FDR took office, averaging 27% below their 1929 level, compared to 18% lower between in 1930-32.The rest of their article explains how the New Deal created the above numbers. There is nothing new in their story, but their numbers certainly are interesting. I am looking forward to reading what Eric Rauchway, Brad DeLong, Paul Krugman and others have to say in response to this piece. Please guys, don't dissapoint me.

Even comparing hours worked at the end of 1930s to those at the beginning of FDR's presidency doesn't paint a picture of recovery. Total hours worked per adult in 1939 remained about 21% below their 1929 level, compared to a decline of 27% in 1933. And it wasn't just work that remained scarce during the New Deal. Per capita consumption did not recover at all, remaining 25% below its trend level throughout the New Deal, and per-capita nonresidential investment averaged about 60% below trend. The Great Depression clearly continued long after FDR took office.

If you are interested, the Ohanian and Lee data can be found here.

Update: Eric Rauchway replies here. Among other things, he notes Ohanian and Lee's critique is narrowly focused on the NRA and ignores New Deal policies that did work (e.g. devaluing the dollar, not sterilizing gold inflows, and shoring up banks).

Update II: Brad DeLong provides a great response here.

Sunday, February 1, 2009

Samuel Brittan on Deflation

Too much that passes for financial comment is preoccupied with the bogey of deflation when it ought to be concerned with the reality of slump.If I read Brittan correctly, he is saying we should focus on the source of the problem--the slump--not the symptom of it. Sounds like Brittan would be sympathetic to a nominal income target for monetary policy. Brittan also makes this interesting comment:

Some of the same short-fused commentators who now blame Alan Greenspan, the former Federal Reserve chairman, for overstimulating the US economy [in the early-to-mid 2000s] were then screaming for him to do more to offset the threat of deflation.Brittan goes on to talk more about deflation, including the mention of an article I really enjoyed reading.

The Incredible Collapse of U.S. Domestic Demand

Excluding government spending, domestic demand declined even more at a rate of approximately 11% in 2008:Q4. Given the nominal rigidities--sticky prices--that exist in the U.S. economy, this incredible collapse of U.S. domestic demand does not bode well for the economy moving forward. Maybe I missed it, but it seems this development should be getting more attention.

Update: The above graph is in nominal terms. On a real basis the collapse in domestic demand is still large but no longer the biggest one since WWII.