I want to come back to one of the points from my last

post. There I noted the global economy was hit by a series of large positive supply shocks beginning in the mid-1990s: the rapid advances in technology and the opening up of Asia. The former raised productivity while the latter increased the world's labor supply. Both pushed up the return to capital and put downward pressure on global inflation.

This run of positive supply shocks continued into the 2000s--productivity growth peaked between 2002 and 2004--but was interrupted by the Great Recession. It now appears to be returning to full stride. This time, though, the supply shocks are not coming from further increases in the global supply of labor, but from further technological advances. The increased digitization, automation, and overall smart-machining of our economy is and will continue to bring huge productivity gains. For example, by the end of 2016 there will be

30 U.S. cities with driverless cars, artificial intelligence will be

diagnosing illness, and 3D printers will be making

practically everything including themselves. And oh yea, robots will be

delicately picking fruit. These examples highlight what Erik Brynjfolsson and Andrea McAfee call

the second machine age where we will see rapid productivity growth that will reinforce the high return to capital.

How the world handles this second machine age over the next few decades will be, in my view, one of the biggest economic challenges going forward. Rapid technological advances are ultimately good for long-run growth, but in the short run they can be very disruptive to many jobs and industries. This has always been true, but the pace and size of these disruptive supply shocks are likely to increase. It is true that we do not see much evidence in the data yet for this process, but I chalk that up to

measurement problems and that we are only the cusp of these changes. In any event, I suspect that this issue will make the present-day concerns over secular stagnation, liquidity traps, saving gluts, and the Japanification of Europe look quaint.

One widely-held concern about large positive supply shocks is that they will shift income from labor to capital. This concern can be seen in this

The Economist's discussion of the Asian supply shock back in 2005:

China's impact on the world economy can best be understood as what economists call a “positive supply-side shock”. Richard Freeman, an economist at Harvard University, reckons that the entry into the world economy of China, India and the former Soviet Union has, in effect, doubled the global labour force (China accounts for more than half of this increase). This has increased the world's potential growth rate, helped to hold down inflation and triggered changes in the relative prices of labour, capital, goods and assets.

The new entrants to the global economy brought with them little capital of economic value. So, with twice as many workers and little change in the size of the global capital stock, the ratio of global capital to labour has fallen by almost half in a matter of years: probably the biggest such shift in history. And, since this ratio determines the relative returns to labour and capital, it goes a long way to explain recent trends in wages and profits.

The trends, of course, being the higher share of income going to capital and the slow growth of real wages. It is a natural consequence, the article argues, of the higher returns to capital generated by such supply shocks. The rapid technological advances, therefore, will only reinforce these developments since they too raise the return to capital. Woe is the labor share of income.

Another related concern is that that this growth in global capacity will not be matched by sufficient demand given the declining share of income going to labor. There will be a persistent demand shortage as argued Dan Alpert in his "

Age of Oversupply". He worries there will be a persistent global glut.

So what should be done? Left-of-center solutions range from more government spending to make up for the spending shortfall to a basic income policy to offset the decline in labor's share of income. One of the more interesting proposals, in my view, from the left is to have the federal government invest in the SP500 on behalf of its citizens. Any earnings from this investment would be distributed among households. This would make everyone a capitalist and thereby empower them to benefit from the gains of the second machine age.

Eric Lonegran and Mark Blyth, for example,

argue the U.S. government should create a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) to do just that. They would have the federal government sell more treasury securities to fund the SWF which would then invest the funds in a stock market index fund. The earnings would be sent to its shareholders, U.S. taxpayers. From a macro-finance perspective this is a clever idea, but from a political-economy perspective I worry that investing decisions would become very political and messy.

So let me propose another solution, one that allows markets to support growth in labor's share of income. It is a very simple solution: let the price level reflect changes in productivity while stabilizing nominal income growth. Put differently, central banks should aim to stabilize the growth of nominal wages, but ignore changes in the price level. This would allow real wages to more closely follow the rapid productivity growth.

To see how this would work recall the large positive supply shocks from Asia and technology that culminated in the productivity boom of 2002-2004. Both of these developments raised the return to capital and put downward pressure on inflation. All else equal, the higher return to capital should have resulted in a higher market-clearing or 'natural interest rate' while the downward drift in inflation should have supported the growth of real wages. Instead, the Fed offset the decline in inflation by lowering its target interest rate. Given the Fed's

monetary superpower status, this lowering of short-term interest rates was replicated across much of the world. So just as the fundamentals of the global economy were pointing to higher real interest rates and lower inflation, the Fed and other central banks moved in the opposite direction to keep inflation stable. These actions served to raise firm's profits while reducing labor's share of income.

1

Here's why. A permanent rise in productivity means lower per unit production costs for firms. In turn, this means greater profit margins for a given sales price. Firms will respond to this development by building more plants. This expands the productive capacity of the economy and causes, given competitive pressures, firms to lower their sales prices in an attempt to gain market share. Their profit margins, though, should remain relatively stable because the drop in their output prices is matched by a drop in their unit costs of production.

Note that all firms are lowering to varying degrees their output price because of this process. Consequently, the price level, an average of firms’ output prices, will also fall. This spreads the benefits of the productivity gains to all workers through higher real wages. And with these higher real wages workers can provide the demand needed for full employment.

Now imagine central banks respond to this productivity-driven deflation by easing monetary policy, as they would under inflation targeting. Sales prices are stabilized, but given sticky input prices like wages this action also leads to expanded profit margins.

So instead of allowing the productivity gains to be shared with labor through a gently falling price level, monetary policy has instead served to increase the share of income going to capital.

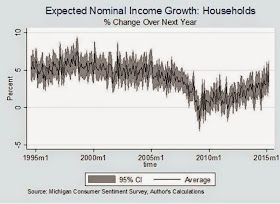

This, in my view, explains a meaningful amount--though not all--of the growth in capital income since the mid-1990s. And my fear is that in the second machine age with rapid productivity growth this trend will worsen. Below is a figure from a recent

paper of mine that lends support to this interpretation:

Now I want to be clear. I am not advocating the malign deflation that comes form a collapse of aggregate demand, as seen in the 1930s. What I am talking about is allowing productivity shocks to be gently reflected in the price level while stabilizing aggregate demand growth. This is a

benign form of deflation and yes,

it has happened.

Under this kind of deflation, the standard problems associated with deflation--the zero lower bound (ZLB), financial intermediation, and real debt burdens--are less of an issue. The higher productivity growth implies a higher real interest rate that should counter the downward pressure on the nominal interest rate and therefore minimize the chance of hitting the ZLB. Financial intermediation should not be adversely affected either, since the burden of any unanticipated increase in real debt coming from the benign deflation would be offset by a corresponding unanticipated increase in real incomes. Collateral values, meanwhile, should not decline but increase given expectations of higher future earnings from the productivity growth.

By keeping output price growth stable, inflation targeting inadvertently contributes to the rising share of income going to capital in periods of rising productivity. So what kind of monetary policy would stabilize aggregate demand growth and allow changes in productivity growth to be reflected in the price level and thus in real wages? The answer is a NGDP target. Under this rule, the Fed would aim to stabilize the growth of total dollar spending (or equivalently nominal income) and quit worrying about changes in inflation. Some like

George Selgin would further focus the Fed target explicitly on the expected growth of nominal wages. Either way, the Fed would let productivity be reflected in the price level.

So a partial solution to the growing income inequality between labor and capital income is to have monetary policy adopt a NGDP target of some kind. For those who have little faith in monetary policy hitting a NGDP target this approach can be

operationalized with the help of fiscal policy.