IT has become part of the accepted history of our time: The bursting of the housing bubble was the primary cause of a financial crisis, a sharp recession and prolonged slow growth. The story makes intuitive sense, since the economic crisis included a collapse in the prices of housing and related securities. The movie “The Big Short,” which is based on a book by Michael Lewis, takes this cause-and-effect relationship as a given.

But there is an alternative story. In recent months, Senator Ted Cruz has become the most prominent politician to give voice to the theory that the Federal Reserve caused the crisis by tightening monetary policy in 2008. While Mr. Cruz (who is an old friend of one of the authors of this article) has been criticized for making this claim, he shouldn’t back down. He’s right, and our understanding of the great recession needs to be revised.

The crux of our story is that what would have been an ordinary recession got turned into the Great Recession because the Fed failed to do its job. Readers of this blog will be familiar with this argument. For those who are not here is a brief recap of the evidence supporting our claims.

First, the Fed contained the fallout from housing crisis for almost two years. This can be seen in the three figures below. The first two figures show that even though housing peaked in early 2006, employment and personal income outside of housing-related sectors actually grew at a stable rate up until about early-to-mid 2008.

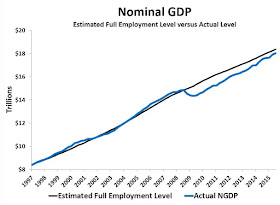

.This third figure shows that nominal spending overall continued to grow fairly stable during the initial run on the shadow banking system, as seen by the Ted spread. That run occurred from occurred from August 2007 to about May 2008. It also shows that the biggest spike in the Ted spread occurs only after the Fed allows nominal spending to start dropping.

Second, the Fed tightened policy in 2008 and did so in two phases. First, beginning around April 2008 the Fed began signalling it was planning to raise interest rates as seen in the figure below. It shows the market expectation of the federal funds rate one year in advance. It rises all the way through the summer of 2008 and remains higher than the actual federal funds rate through October 2008. This is the first phase of tightening in 2008. It was an explicit tightening, albeit of the future path of monetary policy.

The second stage, as we note, in the Op-Ed occurs in the second half of 2008. Here the natural interest rate is falling fast and the Fed fails to lower its target interest rate until October 2008. This is a passive tightening of monetary policy and is reflected in the decline in expected inflation and nominal spending that starts in mid-2008.

To summarize, our argument is that the Fed was doing a decent job responding to the housing bust up until 2008. After that point it tightened monetary policy and catalyzed the reaction that lead to the Great Recession. By the time the Fed changed course in late 2008 it was too late. Interest rates had already cross the zero lower bound (ZLB). Once that happens monetary policy as it is currently practiced cannot do much. (For more on the crossing of the ZLB see my review of Atif Mian and Amir Sufi's book on the crisis. Update: also see this twitter conversation with Amir Sufi on the ZLB.) The central bank of Australia, however, acted sooner and never faced the ZLB problem, despite having a housing and debt bubble too.

For interested readers, I would direct to the work of Richmond Fed economist Robert Hetzel who has written an article and book that makes the same argument. Also, see Scott Sumner's early critique of Fed policy during this time as well.

P.S. Just to demonstrate how worried the Fed was about inflation rather than growth late into the crisis, here is an excerpt from the minutes of the August 2008 FOMC meeting. Note they they were expecting to raise rates at the next meeting.