It is 'recession watch' time again. The May jobs report seems to have awakened the dormant recession concerns that emerged earlier in the year. See, for example, Josh Zumbrun, Jeff Spros, Edward Harrison, and Sam Ro. I was one of those observers who was concerned about a recession in early 2016. But unlike some, I never stopped worrying about it for one big reason: the global reach of Fed policy. It's tightening cycle, which began in mid-2014, has been putting a choke hold on the global economy and this, in turn, has been straining the U.S. economy. This is something the FOMC should keep in mind as it meets this week.

Here is how this has unfolded. First, the Fed began talking up interest rate hikes in earnest in mid-2014. We know this from the 1-year ahead fed fund future rate, which start rising in June 2014. One can also see this by looking to the 1-year treasury yield, which provides as an approximate guide to where interest rates are expected, on average, to go over the next year.1 The blue line in the figure below shows the 1-year treasury yield. Here we see it start to rise in 2014 about the same time the 1-year Euro yield--the red line--begins to fall. In other words, just as the Fed began raising the expected path of interest rates the ECB began doing the opposite. This policy divergence has persisted until this day as seen below:

This policy divergence, unsurprisingly, drove up the trade-weighted dollar with it as seen in the next figure:

The trade-weighted dollar appreciated over 20% between mid-2014 and December 2015. This sharp appreciation of the dollar also meant those countries in the dollar block saw their currencies rise rapidly too. The most important of these countries is China. Its trade-weighted currency closely followed the dollar as seen blow:

As I have noted before, this appreciation of the RMB seems to have been the straw the broke the camel's back in China. The Chinese economy was already slowing down and was laden with the burden of its rapid debt growth since 2008. The Fed's talking of up of interest rates hikes could not have come at a worse time for China. Among other things, it appears to be the key reason for the capital outflow from China during this time.

So the Fed's talking up interest rate hikes put a stranglehold on the dollar bloc countries. Below is a figure from a recent coauthored paper of mine that shows how big the dollar bloc is as percent of the global economy (on a PPP basis). The dollar bloc is far bigger than the next two largest currency blocs. This means Fed policy--including its rate hike talk-- gets transmitted to a large part of the global economy.

Fed policy is also felt abroad for another important reason. There has emerged outside the United States a parallel dollar system where loans and securities are issued in dollars to non-U.S. residents. Credit to non-residents has tripled since 2000 with the dollar share of this growth increasing from 62% to 75% according to BIS data. Here is another figure from my coauthored paper that highlights this fact:

What this means is that when the Fed talks up rate hikes and causes the dollar to surge, it also increases the real debt burden for parallel dollar system outside the United States. This makes the global financial system more vulnerable to U.S. monetary policy. (See here and here for more on this point)

So the Fed's talking up interest rate hikes put a stranglehold on the dollar bloc countries. Below is a figure from a recent coauthored paper of mine that shows how big the dollar bloc is as percent of the global economy (on a PPP basis). The dollar bloc is far bigger than the next two largest currency blocs. This means Fed policy--including its rate hike talk-- gets transmitted to a large part of the global economy.

Fed policy is also felt abroad for another important reason. There has emerged outside the United States a parallel dollar system where loans and securities are issued in dollars to non-U.S. residents. Credit to non-residents has tripled since 2000 with the dollar share of this growth increasing from 62% to 75% according to BIS data. Here is another figure from my coauthored paper that highlights this fact:

What this means is that when the Fed talks up rate hikes and causes the dollar to surge, it also increases the real debt burden for parallel dollar system outside the United States. This makes the global financial system more vulnerable to U.S. monetary policy. (See here and here for more on this point)

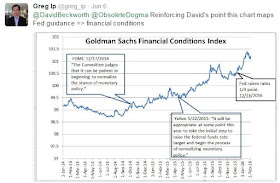

The financial stress that emerged in the late 2015 and early 2016 can arguably be traced back through these two global linkages to the Fed's talking up of rate hikes. Greg Ip provides further corroborating evidence for this view:

Interestingly, not only has the Fed's rate hike talk seem to have resulted in increased financial stress, it also appears to have helped contribute to the sharp drop in oil prices since mid-2014. Both Ben Bernanke and James Hamilton show in separate pieces that about 40-45% of the decline in oil prices since that time can be traced to weak global demand. The obvious candidate is the policy-induced rise of the dollar constricting growth in the dollar bloc countries. If so, the low oil prices reflect as much Fed policy as increase supply.

To be fair, the Fed has being paying more attention to global developments. Just see the March FOMC minutes or this article about Governor Lael Brainard. What it has not been doing (at least publicly) is connecting the dots between its rate hike talk and the problems in the global economy. And until it does so figures like the one below are bound to get worse:

This could be, as Greg Ip notes, the first recession the Fed has caused simply by talking about interest rate hikes. The FOMC should take note.

Related Links

1 Based on the expectation hypothesis view of interest rates which says the long-term rate (here, the 1-year treasury yield) is equal to the average of the short-term rates over the same horizon plus a term premium. Since the 1 year treasury is relatively short-term the term premium here should not be too big. Consequently, the observed yield should largely be the average expected short-term rate over the next year.

HI David,

ReplyDeleteThere was more going on. You mention above that a tightening cycle started in mid-2014. Yet it was really the peak of an effective demand cycle which had been going on for years before that. In 2013, I forecasted the 2014-demand-cycle peak with my effective demand model. The result was exactly what Keynes' effective demand would say; we saw profits peak and top line revenues peak. It was a demand CYCLE peak beyond and including the effects of Fed policy.

You are missing so much of the overall picture by not seeing a US effective demand cycle, which has global impacts.