As readers of this blog know, I

have an interest in the

Fed's operating system. This interest has

culminated in a new paper where I look at the consequences of the Fed moving from a corridor system to a floor system in 2008. In particular, the paper looks at what this change has meant for bank portfolios and, as a result, financial intermediation provided by banks. The paper concludes with some policy recommendations. I would also note that George Selgin has just released a

new book on this topic. My hope is that these projects will help inform the conversation over what operating system the Fed wants as it continues to normalize monetary policy.

Paper Outline

So what does my paper have to say? It starts by laying out the standard arguments for a floor system:

The central idea behind this move was to remove the opportunity cost to banks of holding excess reserves by offering the banks a deposit rate at the Fed—the IOER rate—that was equal to or above short-term market interest rates. This favorable return was to sever banks’ incentive to rebalance their portfolios away from excess reserves toward other assets. The IOER rate was also to put a floor under short-term interest rates so as to align them with the Fed’s desired interest rate target. Together, these two facets of the floor system would allow the Fed to use its balance sheet as a tool of monetary policy while still maintaining interest rate control.

In this new operating system, the stance of monetary policy was no longer set by a market interest rate but by an administrative interest rate: the IOER rate. The stance of monetary policy also was no longer tied to the supply of reserves. Instead, it was linked to the quantity of reserves demanded by banks, which the Fed influenced through changes to IOER. Specifically, the Fed set the IOER rate high enough that banks’ demand for reserves became perfectly elastic with respect to the federal funds rate. As a result, changes in the quantity of reserves supplied led to identical changes in the quantity demanded, other things being equal.

The Federal Reserve, in short, went from an operating system in which monetary policy was transmitted through open market operations to one in which it is transmitted through the IOER rate. The Fed’s operating system

changed from one in which money, in the form of reserves, mattered for monetary

policy to one in which money has been “divorced” from monetary policy.

Okay, so why does this "divorce" matter? For advocates of a floor system the answer is simple:

This divorce from money is seen by many observers as the key advantage... because it gives the Fed the freedom to use its balance sheet independently of its desired interest rate target. The Fed, for example, can now sharply increase the supply of reserves in response to a liquidity crisis without causing a decline in its targeted interest rate.

Skeptics of the floor system, on the other hand, see this divorce as more problematic:

Others, however, see this divorce as creating an operating system that impairs the transmission mechanism of monetary policy... These observers’ understanding starts with the standard assumptions of a floor system. First, a floor system requires the IOER rate to be set at least equal to short-term interest rates. This removes the opportunity costs to banks of holding reserves and thereby keeps their demand perfectly elastic with respect to other short-term interest rates...

[This] can lead to a rebalancing of bank portfolios that causes the supply of loans to be lower than it would have been otherwise. Banks lend as long as the marginal cost of funding is less than the risk-free marginal return on bank lending. In the Fed’s floor system, the IOER rate sets the marginal funding cost. Consequently, by setting the IOER rate higher than other short-term interest rates, the Fed has raised the marginal costs of funding and narrowed the gap between these costs and the risk-free marginal return on bank lending. All else being equal, the narrowing of this gap implies a relative reduction in the supply of loans and therefore a relative decline in the money supply.

Are these worries merited? My paper provides an empirical look at bank portfolios before and after the advent of the floor system to see if (1) there have been big structural shifts in bank balance sheets consistent with the critics claims and (2) whether such shifts can be attributed to the Fed's floor system.

Empirical Evidence

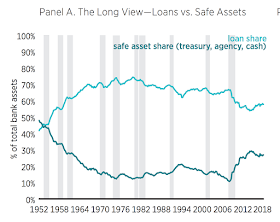

On (1) I start with the following figure. It shows the share of bank assets allocated to loans and to safe assets (defined as the sum of cash, treasury, and agency asset holdings). Unsurprisingly, these series are almost mirror images of each other over both cyclical and structural time horizons. They tend to move in opposite directions during recessions--the grey bars--and over longer periods. At the advent of the floor system in late 2008, the loan share began declining as the safe asset share started rising. This change has been sustained and only recently has started reversing:

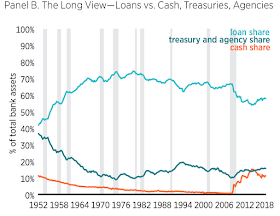

If we break the safe assets apart into its subcategories, we see that that this tight link has been historically driven by movements in treasury and agency investments corresponding with changes in the loan share. Since 2008, the driving force behind the tight link became cash not treasury and agency investments:

If we zoom in and use two scales, this apparent structural change is even clearer. Cash shares and loan shares become mirror images of each other:

Something big happened in 2008 that continues to the present that caused banks to allocate more of their portfolios to cash assets and less to loans. While the financial crisis surely was a part of the initial rebalancing, it is hard to attribute what appears to be 10-year structural change to the crisis alone. Instead, it seems more consistent with the critics view that the floor system itself has fundamentally changed bank portfolios allocation.

That takes us to question (2). The following figure shows the loan share of bank assets plotted against the spread between the IOER rate and the overnight dollar Libor rate. This IOER-Libor spread is negatively and strongly correlated with the loan share. This suggests banks invested less in loans when the relative return on bank reserves rose and vice versa.

Conversely, banks appear to have allocated more to cash assets with the IOER-Libor spread rose and vice versa:

The paper goes on to more carefully test these relationships using two-stage least squares regressions that control for endogeneity issues and other confounding influences. Moreover, the paper also provides a further breakdown of this relationship among foreign banks, large domestic banks, and small domestic banks. Collectively, the regressions point to a strong causal effect running from the IOER-Libor spread to the allocation of bank assets.

The Fed's move to a floor system, then, does seem to have influenced the amount of financial intermediation provided by banks to the private sector. The end of the paper provides some counterfactual exercises, including the following figure

This counterfactual shows the supply of bank loans would have been, at its peak, as much as $2 trillion higher in 2014. By mid-2018, with the IOER-Libor spread shrinking, it was closer to a $1 trillion shortfall. Now to be fair, other factors such as increased risk aversion, fintech, and new regulations also contributed to below trend growth in bank lending since the crisis. Still the evidence strongly suggest that financial intermediation to the private sector through banks declined because of the floor system.

Policy Implications

The Fed's floor system, in short, has caused banks to increase their investment in the Fed at the expense of investing in the private sector. The question, then, becomes whether the Fed is any better than banks in allocating this credit. Put differently, is the Fed as a financial intermediary--funding short and lending long--really providing a better financial service than would have been provided by the private sector financial firms? It is not obvious to me that the answer is yes.

What is obvious to me is that the Fed's floor system creates a whole set of other problems. First, as a profitable financial intermediary, the Fed is setting itself up for political shenanigans. Recall

Congress taping into the Fed's capital surplus in 2018 and 2015. Though these transfers were relatively small and to some extent accounting gimmicks, they show how tempting a large, profitable Fed balance sheet can be to Congress. Second, the floor system effectively destroyed unsecured interbank lending. This market provided useful interbank monitoring and price discovery that no longer exists. Bringing this market-based monitoring back would be a nice addition to the bank regulator's existing toolbox. Third, the floor system forces the Fed to take safe asset collateral off the market which impairs other parts of the financial system. Only recently has President Trump's budget deficits

begun to fill this hole. Fourth, the floor system can create bad optics for the Fed via the appearance of large 'subsidies' to large and foreign banks. In this era of populist politics, the Fed should be worried about the dangers to its independence this image could create. Finally, as noted above, I worry the Fed is a less effective financial intermediary than the private sector.

In short, I see the costs exceeding any benefits from the floor system. That is why I advocate a return to a corridor system, but this time with the IOER explicitly setting the lower boundary. That is, the IOER would still be around, but it would be set lower than overnight market interest rates. For the past decade it has been for the most part above them. More details are in the paper.

Update: I have had several commentators ask me about the difficulty of returning to a corridor system given the relatively new LCR. Let me quote

Governor Randy Quarles from a recent speech:

How banks respond to the Fed's reduction in reserve balances could, in theory, take a few different forms. One could envision that as the Fed reduces its securities holdings, a large share of which consists of Treasury securities, banks would easily replace any reduction in reserve balances with Treasury holdings, thereby keeping their LCRs roughly unchanged. According to this line of thought, because central bank reserve balances and Treasury securities are treated identically by the LCR, banks should be largely indifferent to holding either asset to meet the regulation. In that case, the reduction in reserves and corresponding increase in Treasury holdings might occur with relatively little adjustment in their relative rates of return.

In other words, since reserves and treasuries are viewed as equal HQLA there could be a substitution between the two as the Fed shrinks its balance sheet down. Quarles notes that currently some banks favor reserves, but that tells us nothing about what is ideal or what would transpire in a new symmetric corridor system. Finally, it is also worth noting that banks can use Treasuries, but not reserves, as collateral for repos. Manhoman Singh is very good on that point. So Treasuries can actually make banks more liquid that non-hypothecatable reserves.

P.S. Here is a panel from the recent Cato Monetary Policy Conference on this issue. Great comments from Stephen Williamson, George Selgin, and Peter Ireland. Josh Zumbrum was the moderator.