What do John Cochrane, Paul Krugman, and Scott Sumner have in common? A lot more than you think. It would be easy to conclude otherwise based on the macroeconomic debates these three individuals have engaged in since the onset of the Great Recession. Each has certainly pushed a distinct policy objective, but underlying their macroeconomic prescriptions is an edifice of understanding that is complementary and points to a fundamental agreement among them on the key determinants of aggregate demand.

This commonality among them became clear to me over the past few months as I was reading and thinking about what it takes to generate robust aggregate demand growth in a depressed economy. John Cochrane's 2011 European Economic Review

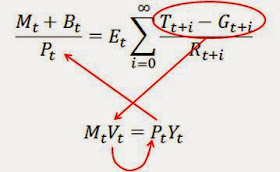

article in particular helped me make the connections and was the inspiration for the above figure I sketched over the Thanksgiving holiday. This figure highlights the differences among them, but also points to their commonality via the two equations in the genie bottle. These equations come from the Cochrane paper and go a long way in helping one make sense of how monetary and fiscal policy interact and affect aggregate demand. Consequently, they help

clarify some of the questions on Neo-Fisherism that have recently generated.

So what exactly do these two equations tell us? To answer this question let's look closer at these equations:

The first term is a stripped-down intertemporal government budget equation. The left-hand side shows the current monetary base (Mt) and current government bonds (Bt) divided by the price level (Pt). The right-hand side shows the discounted present value of all expected future government surpluses [i.e. it shows the present value of expected future tax revenues (Tt+i) minus expected future government expenditures (Gt+i)]. This equation tells us that in order for the current stock of government debt to maintain its value the public must expect future budget surpluses be large enough to pay it off.

The second term is the equation of exchange. It simply shows that the monetary base (Mt) times how often it is used [or its velocity (Vt)] equals total dollar spending on output (PtYt).

With these two equations one can demonstrate both the fiscal theory of the price level (FTPL) and the more common monetary theory of the price level (MTPL). Now John Cochrane uses this framework to motivate the FTPL view, but Scott Sumner could also use to think about the MTPL. Paul Krugman, who often invokes both views, could use it too. One of the big takeaways is that the FTPL and MTPL should be seen as complementary views of price level. This can be seen by taking a closer look at each theory.

Consider first the FTPL. This is how Cochrane

summarizes this view in light of the two equations:

The fiscal equation affects prices in an intuitive way. If people start to think surpluses will not be sufficient to pay off the debt, they try to unload government debt now, buying other assets or goods and services. This is just “aggregate demand.”

In other words, if expected future budget surpluses suddenly decline, people will start unloading government bonds in anticipation of them loosing value. This will cause the velocity of money to increase as portfolios are rebalanced away from public debt and, in turn, cause the price level to raise. Note that the stock of money does not change (though its velocity does). Hence, its FTPL name. In terms of the equations, The figure below shows the causality through the two equations.

Episodes of hyperinflation provide strong evidence for this view. John Cochrane, however, is concerned that this process might also unfold in the United States given the large run up of public debt over the past five years. He worries that the U.S. fiscal credibility might unravel if the growing public debt is left untouched.

Paul Krugman shares Cochrane's belief in the FTPL, but notes that it also implies that there could

too much fiscal credibility. If so, it would be creating a drag on aggregate demand growth (i.e. higher expected future surpluses imply lower velocity today and, in turn, mean lower aggregate demand growth). While this argument may apply to the United States, Krugman is certain it applies to Japan. Here is Krugman

discussing the proposed tax hikes in Japan:

I see no prospect that Japan will put off the tax hike forever. But even if it were true, this is credibility Japan wants to lose.

After all, suppose

investors conclude that Japan will never raise taxes enough to service

its debt. What would they think would happen instead? Not default —

Japan doesn’t have to default, because its debts are in its own

currency. No, what they might fear is monetization: Japan will print

lots of yen to cover deficits. And this will lead to inflation. So a

loss of fiscal credibility would lead to expectations of future

inflation, which is a problem for Abe’s efforts to, um, get people to

expect inflation rather than deflation, because … what?

Long ago I argued that

what Japan needed was a credible promise to be irresponsible. And

deficits that must be monetized are one way to make that happen...

Interestingly, John Cochrane the made the same point in his 2011 paper:

The last time these issues came up was Japanese monetary and fiscal policy in the 1990s... Quantitative easing and huge fiscal deficits were all tried, and did not lead to inflation or much‘‘stimulus’’. Why not? The answer must be that people were simply not convinced that the government would fail to pay off its debts. Critics of the Japanese government essentially point out their statements sounded pretty lukewarm about commitment to the inflationary project, perhaps wisely. In the end their ‘‘quantitative easing’’ was easily and quickly reversed, showing those expectations at least to have been reasonable.

As I said earlier, Paul Krugman and John Cochrane have a lot more in common than you think. Along these lines, one can see why the modest tax increase this year could had such large effect on the Japanese economy. The tax hike signaled the government's commitment to future surpluses and that, rather than the tax hike itself, may have stalled aggregate demand.

Even though Krugman and Cochrane may agree on the mechanism and its potential to raise aggregate demand, their policy prescriptions are different. Krugman would like to have countries like the United States and Japan ease up a bit on fiscal credibility as a way to shore up aggregate demand growth, whereas as Cochrane sees such discretionary moves as potentially destabilizing. Cochrane is concerned doing so might let the aggregate demand genie out of the bottle in an uncontrollable manner.

That it is where Scott Sumner and his push for level targeting becomes important. A level target, specifically a NGDP level target, would get Krugman the aggregate demand growth he wanted without letting the aggregate demand genie out of the bottle in an uncontrollable manner. A NGDP level target, in a depressed economy, would

temporarily allow rapid catch-up growth in aggregate demand until it hit its targeted growth path. And since a NGDP level target would be radical regime change for monetary policy, its adoption would require enough political consensus such that fiscal policy would play a supportive role.

This takes us to the standard MTPL. It says that independent of what fiscal policy is doing, the path of the price level is also determined by permanent changes to the monetary base. It would causally operate through the two equations as follows (note the equality still holds in the first equation):

Scott Sumner's call for NGDP level targeting is implicitly a call for a permanent expansion of the monetary base if needed. Paul Krugman has also explicitly

called for a permanent expansion of the monetary base. These calls are endorsements of the MTPL. Note that the

Fed's QE programs have not been permanent expansions of the monetary base and this explain why their effect on aggregate demand has been muted.

John Cochrane also believes that a permanent increase in the monetary base would raise aggregate demand and the price level. He, however, only believes this is possible if the monetary policy is allowed to permanently monetize the debt. And that decision, he says, is really a fiscal one. Hence, he sees the MTPL as just a special case of FTPL. Here he is explaining this point in the context of helicopter drops:

Suppose

a helicopter drop is accompanied by the announcement that taxes will be

raised the next day, by exactly the amount of the helicopter drop. In

this case,everyone would simply sit on the money, and no inflation would

follow. The real-world counterpart is entirely possible. Suppose the

government implemented a drop, repeating the Bush stimulus via $500

checks to taxpayers, but with explicit Fed monetization. However,we have

all heard the well-explained ‘‘exit strategies’’ from the Fed, so

supposing the money will soon be exchanged for debt is not unreasonable.

And suppose taxpayers still believe the government is responsible and

eventually pays off its debt. Then, this conventional implementation of a

helicopter drop,in the context of conventional expectations about

government policy, will have no effect at all.

Thus,

Milton Friedman’s helicopters have nothing really to do with money.They

are instead a brilliant psychological device to dramatically communicate

a fiscal commitment, that this cash does not correspond to higher

future fiscal surpluses, that there is no ‘‘exit strategy’’, and the cash

will be left out in public hands... The

larger lesson is that, to be effective, a monetary expansion must be

accompanied by a credibly communicated non-Ricardian fiscal expansion as

well. People must understand that the new debtor money does not just

correspond to higher future surpluses. This is very hard to do—and even

harder to do just a little bit.

So here again Cochrane is speaking to Krugman's concerns about there being too much fiscal credibility. In this case it is preventing the Fed from doing what needs to be done to get out of a recession.

I disagree with Cochrane that the MTPL is just a special case of the FTPL. First, on a practical level the Fed has effectively been doing one long helicopter drop since its inception and never has had to worry about fiscal policy. Over time as the economy has grown the Fed has permanently increased the monetary base and done so through permanent open market operations. That is, it has permanently expanding its balance sheet as seen in the figure below. So it is not clear that should the Fed attempt to permanently increase its monetary base (say as part of a transition to a NGDP level target or a higher inflation target) that fiscal policy would offset it.

Second, the Fed is not limited to purchasing just treasury securities. It can also buy foreign exchange, among other assets. So even if expected future budget surpluses were increasing the Fed could still increase the monetary base through foreign exchange purchases. This is what the Bank of Israel did during the crisis.

In short, the FTPL and MTPL can be seen as separate but complementary determinants of the price level working through common mechanisms. And this is why John Cochrane, Paul Krugman, and Scott Sumner have much more in common than you might imagine.