Kenneth Kuttner has a new

paper that reexamines the relationship between the Fed's interest rates and house prices during the housing boom. The paper is receiving

some attention because it claims that the existing literature on this topic collectively shows only a small role for interest rates on the housing prices. Here is Kuttner:

All available evidence — existing studies, plus the new findings presented above — points to a rather small effect of interest rates on housing prices. VAR-based estimates of the effect of a 25 basis point expansionary monetary policy shock range from 0.3% to 0.9%, both in the U.S. and in other industrialized countries....they are too small to explain the previous decade’s tremendous real estate boom in the U.S. and elsewhere.

Looking back it is clear that there were other developments that contributed to the housing boom like financial innovation, global demand for safe assets, poor

governance, industry structure, housing policy, and misaligned creditor

incentives. Contrary to the Kuttner's claim, however, this does not mean that the contribution of the Fed's low interest rates were trivial. Here are the reasons why.

First, to really learn the full impact of the low interest rates one needs to also consider their indirect effect on housing. One indirect effect of the Fed's low interest rate policy is that it influenced financial innovation and the demand for safe assets which further lowered yields. When the Fed pushed interest rates low, held them there, and promised to keep them there for a "

considerable period" in 2003 it created new incentives for the financial system. First, via the expectations hypothesis (which says long-term interest rates are simply an average of short-term interest rates over the same period plus a term premium) these developments pushed down medium to longer yields as well, as seen in the figure below:

As Barry Ritholtz

notes, this drop in yields caused big problems for fixed income fund managers who were expected to deliver a certain return. Consequently, there was a "search for yield" or as Ritholtz says these managers of pension funds, large trusts, and foundations had to "scramble for yield." They needed a higher but relatively safe yield in order to meet their expected return. The U.S. financial system meet this rise in demand by transforming risky assets into safe, AAA-rated assets.

The Fed's low interest rate policies also increased the demand for safe assets for hedge fund managers. For them the promise of low short-term interest rates for a "considerable period" screamed opportunity. As Diego Espinosa shows in a forthcoming paper, these investors saw a predictable spread between low funding costs created by the Fed and the return on higher yielding but safe assets. They too wanted more AAA-rated assets to invest in so that they could take advantage of this spread that would be around for a "considerable period." Here too, the U.S. financial system responds by transforming risky assets into safe assets.

There is another way the Fed's low interest rate policy increased the demand for safe assets during the housing boom. The Fed controls the world's main reserve currency and many emerging markets are formally or informally pegged to dollar. Thus, its monetary policy is exported across much of the globe--it is a

monetary superpower. This means that the other two monetary powers, the ECB and the Bank of Japan, are mindful of U.S. monetary policy lest their currencies becomes too expensive relative to the dollar and all the other currencies pegged to the dollar. As as result, the Fed's monetary policy gets exported to some degree to Japan and the Euro area as well. In the early-to-mid 2000s, those dollar-pegged emerging economies pegged were forced to buy more dollars when the Fed loosened monetary policy with its low interest rate policies. These economies then used the dollars to buy up U.S. debt. This increased the demand for safe assets. To the extent the ECB and the Bank of Japan were also responding to U.S. monetary policy, they too were acquiring foreign reserves and channeling credit back to the U.S. economy. Thus, the easier U.S. monetary policy became the greater the demand for safe assets and the greater the amount of recycled credit coming back to the U.S. economy. This is an important but overlooked point in most discussion about how the Fed's low interest rates contributed to the housing boom.

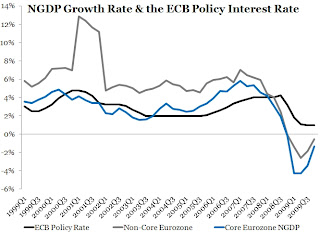

Second, the claim that "all available evidence" point to a small effect ignores some studies that actually reach the opposite conclusion. For example, there are

two studies by Rudiger Ahrend et. al that show low interest rates, specifically ones lower than those prescribed by the Taylor Rule, in conjunction with rapid financial innovation were very important to the housing boom for most of the OECD countries. Here is one graph from the papers that makes this point:

Another study that finds contrary evidence is

Eickmeier and Hofmann (2010) who use a factor-augmented VAR to show that monetary policy not only affected house prices, but also credit spreads and debt levels.

Third, one problem with using VARs for this analysis, as is done in the Kuttner paper, is that they show the effect of a monetary policy shock. Such shocks, however, have become notoriously hard to identify over the past few decades in VARS because Fed actions have become so much more transparent and predictable, and also because monetary policy has become better at responding to output shocks (at least prior to the Great Recession). As a result, shocks to the federal funds rate show much milder effects on other variables (See

Boivin and Giannoni, 2006). Also, even if one is capable of properly identifying shocks, it seems the real problem was more the sustained shift in monetary policy--the 2002-2004 easing cycle--that cannot really be called a shock per se. Maybe one can call it a series of shocks or change in systematic monetary policy, but the point is not to look at one impulse response function and draw conclusions, but look at the cumulative effect of this easing cycle and its contribution to the housing boom. The

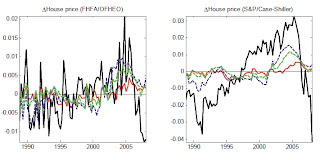

Eickmeier and Hofmann (2010) study does just that. Among other things, it runs a counterfactual experiment that allows the authors to see what part of the housing price boom can be attributed to the Fed's actions, both shocks and systematic policy. Here is what they find:

The blue line is the combined effect of shocks and systematic policy on housing prices. The OFHEO house price index shows a large amount of the surge in home prices is because of monetary policy, while the Case-Shiller index shows somewhat smaller but still meaningfully large role for the Fed. In both cases, monetary policy only matters for the early-to-mid 2000 period. And that is what most critics have been arguing: the Fed's policies in early-to-mid 200s contributed to housing boom of that period.

Now Kuttner's view may one day be vindicated, but before that it happens the above points need to be addressed.