After six years of low interest rates many yields are now crossing the zero percent boundary. Interest rates in Europe and Australia have turned negative on some government and corporate bonds. The decline of these interest rates into negative territory has caused much consternation among two groups of observers.

The first group astonished by this development are those who believed interest rates were pegged by the 'zero lower bound' (ZLB). Interest rates were not supposed to go below zero percent because one could always hold physical cash and earn zero percent rather than holding bank accounts that earned a negative interest rate. Consequently, a breaching of the ZLB has been mind-blowing for some folks. Here, for example, is

Matt Yglesias:

Something really weird is happening in Europe. Interest rates on a range of debt... have gone negative.In my experience, ordinary people are not especially excited about this. But among finance and economic types, I promise you that it's a huge deal — the economics equivalent of stumbling into a huge scientific discovery entirely by accident.

Paul Krugman similarly

observes that crossing the ZLB is something he never expected. While many are surprised, the key idea behind the ZLB still holds. At some point it will become worthwhile to hold cash rather than bank deposits earning a negative return. It is just not at zero percent because of storage costs as recently noted by

Evan Soltas and

David Keohane. So if interest rates continue to fall they will eventually hit the

effective lower bound and currency demand will soar.

It is worth pointing out that

JP Koning has been making this point about storage costs and the ZLB for a long time. For example, he had a

post back in 2014 discussing the implications of the ECB's large €500 note for ZLB:

The ECB has differentiated itself from almost all other developed country central banks by issuing a mega-large note denomination, the €500 note... The €500 note creates a uniquely European problem because its large real value reduces the cost of storing cash and therefore raises the eurozone's lower bound. Think about it this way. To get $1 million in cash you need ten thousand $100 bills. With the €500 note, you need only 1,545 banknotes, or about one-eighth the volume of dollar notes required to get to $1 million. This means that owners of euros require less vault space for the same real quantity of funds, allowing them to reduce storage costs as well as shipping & handling expenses. In other words, the €500 note is far more convenient than the $100 note, the €100, the £100, the ¥10,000, or any other note out there (we'll ignore the Swiss). Thus if Draghi were to reduce rates to -0.25%, or even -0.35%, the existence of the not-so-inconvenient €500 very quickly begins to provide a very worthy alternative to negative yielding ECB deposits. The lower bound isn't so low anymore.

All the more reason to remove the €500 note in order to provide the ECB with further downward flexibility in interest rates. If the existence of the €500 note means that Draghi can't push rates below, say, -0.35% without mass cash conversion occurring... but the removal of said note from circulation allows him to drop that rate to -0.65% before the cash tipping point, then he's bought himself an extra three rate reductions by removing the €500.

So in addition to its

problematic monetary policy, the ECB also has a €500 note that makes it harder for interest rates to reach their market-clearing levels. (Yes, this is a currency union that seems designed for failure.) Institutional details matter and JP Konign is one of the best on this when it comes to monetary policy.

So the ZLB is still binding in spirit if not exactly at zero percent. Fortunately, there are ways to get around it without

eliminating currency.

The second group that finds the move into negative interest rates unsettling do so for a different reason. They see it as another step by central banks to artificially push down interest rates. This is problematic for some, like Bill Gross, because it means

financial markets are being distorted. For others, like Robert Higgs, the low-interest rate policy is troubling because it is causing the

immiseration of people living on interest income.

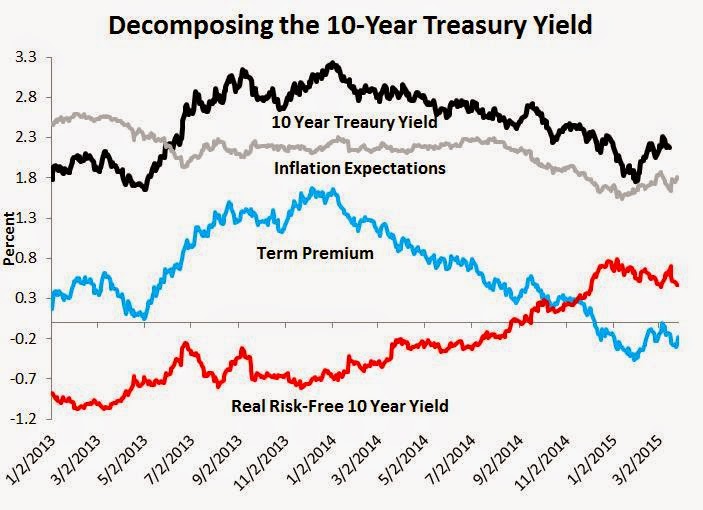

In both cases the premise is that central banks are causing interest rates to remain low. But this premise assumes too much. It could be the case that central banks over the past six years were adjusting their interest rate targets to match where the market-clearing or 'natural' interest rate was going. That is, as the economy weakened interest rates naturally would have fallen and, given the severity of the crisis, may have gone well below zero. Central banks were simply attempting to follow the market-clearing interest rate down, but decided to stop at zero percent because they believed they could not go any further. Even though we now know monetary authorities had some wiggle room left beneath zero percent, they still would have been constrained by the effective lower bound had they kept pushing.

The irony of this is that the Bill Gross and Robert Higgs of the world, who usually are free-market advocates, should be in favor of allowing interest rates to fall when necessary. They believe in the power of prices to clear markets, so they should be open to the possibility that sometimes--in severe crises

like the Great Depression or Great Recessions--interest rates may need

to go negative in order to clear output markets. If so, it is incorrect for them

to ascribe the low interest rates to Fed policy since it was

simply chasing after a falling natural interest rate.

This understanding also means that the effective lower bound on interest rates is a price floor that distorts markets. And any good capitalist worth his salt should be in favor of abolishing this price floor and allowing prices to work. On this point, Paul Krugman is a better capitalist than Bill Gross or Robert Higgs since Krugman believes interest rates are low because of the economy, not the Fed.

That the market-clearing interest rate turned negative over the past six has been borne out in multiple studies. One prominent study that shows this is a 2012

Peter Ireland paper in the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking. Another example comes from Michael Darda of

MKM Partners. He estimates the market clearing interest rate by looking at the historical relationship between the federal funds rate and slack in the prime-age working force plus a risk premium. His estimated market clearing interest rate--the estimated Wicksellian equilibrium nominal short rate--also shows a negative value over this period.