Ben Bernanke delivered a

speech Friday where he further developed his global saving glut (GSG) hypothesis. This view holds that the reason for the low long-term interest rates in the United States during the early-to-mid 2000s was that desired saving vastly exceeded desired investment in emerging economies. Consequently, capital flowed from these countries to the U.S. economy and pushed down long-term interest rates. The cheaper credit in turn fueled the U.S. housing boom. Based on a new research

paper, Bernanke extends his GSG hypothesis by considering the type of assets desired by these emerging economies as they invested in the U.S. economy. He shows that investors from these countries, as well as from Europe, had a strong appetite for AAA-rated assets which were in short supply elsewhere. Given the limited supply of Treasury and agency securities, the U.S. financial system responded by transforming risky assets into safe assets.

And so, we have a theory that nicely ties together global economic imbalances, developments in structured finance, and the U.S. housing boom. Note, though, that the GSG hypothesis places no culpability on the Fed. Instead, blame is placed on the failings of the U.S. private sector and foreigners who save too much. How convenient for Ben Benanke and the Fed. I am trying to be open minded here but really, how can one not view this self-serving explanation with some skepticism? Is this speech really about shedding light on the housing boom or is about defending the Fed? Robin Harding of the FT

thinks it is the later:

Mr Bernanke’s goal, I think, is to strike another blow in the long-running argument about whether it was foreign currency manipulation/excess savings or bad US monetary policy that caused US interest rates to be so low in the middle of the last decade and thus stoked the housing bubble.

But let's give Bernanke benefit of the doubt. Maybe he is just extending his GSG hypothesis and is not trying to absolve the Fed of responsibility for the housing boom. If so, it would do a world of good if he would actually address the tough questions that skeptics like me have about the GSG hypothesis. In case he is reading, here are the questions.

(1)

Wasn't some of the excess saving coming from the emerging economies simply recycled U.S. monetary policy? As Bernanke's speech suggests and as acknowledged by other Fed officials including

Janet Yellen, the Fed is a monetary superpower. It controls the world's main reserve currency and many emerging markets are formally or informally pegged to dollar. Thus, its monetary policy is exported across much of the globe. This means that the other two monetary powers, the ECB and the Bank of Japan, are mindful of U.S. monetary policy lest their currencies becomes too expensive relative to the dollar and all the other currencies pegged to the dollar. As as result, the Fed's monetary policy gets exported to some degree to Japan and the Euro area as well.

In the early-to-mid 2000s, those dollar-pegged emerging economies pegged were forced to buy more dollars when the Fed loosened monetary policy. These economies then used the dollars to buy up U.S. debt. This channeled credit to the U.S. economy and pushed down interest rates. To the extent the ECB and the Bank of Japan were also responding to U.S. monetary policy, they too were acquiring foreign reserves and channeling credit back to the U.S. economy. Thus, the easier U.S. monetary policy became the greater the amount of recycled credit coming back to the U.S. economy.

Now this doesn't mean all of the foreign reserves buildup was due to U.S. monetary policy. There are both precautionary and mercantilist reasons for the accumulation of foreign reserves. U.S. monetary policy affects foreign reserves buildup through the latter one. The question, then, is how important was the mercantilist motive? The two figures below suggest it was and still is sizable. The first figure shows the year-on-year growth rate of global foreign reserves along with the Taylor rule gap. This gap is the difference between the Taylor-rule prescribed federal fund rate and the actual federal fund rate. In other words, the Taylor rule gap provides a measure of the stance of U.S. monetary policy.

The next figure shows the scatterplot of these two series:

This latter figure indicates that about half of the foreign reserves buildup can be tied to the stance of U.S. monetary policy via the mercantilist motive. Now this is not conclusive evidence, but at a minimum it should give GSG supporters pause. It seems that a sizable portion of the saving glut was simply recycled U.S. monetary policy.

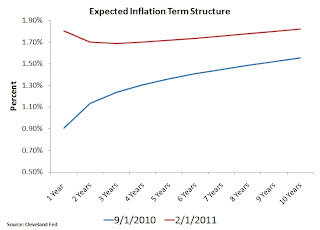

(2) Didn't the Fed itself create some of the increased demand for safe assets by pushing short-term interest rates super low and promising to hold them there for a "considerable period?" When the Fed pushed interest rates low, held them there, and promised to keep them there for a "considerable period" it created new incentives for the financial system. First, via the expectations hypothesis (which says long-term interest rates are simply an average of short-term interest rates over the same period plus a term premium) these developments pushed down medium to longer yields as well, as seen in the figure below:

As Barry Ritholtz

notes, this drop in yields caused big problems for fixed income fund managers who were expected to deliver a certain return. Consequently, there was a "search for yield" or as Ritholtz says these managers of pension funds, large trusts, and foundations had to "scramble for yield." They needed a higher but relatively safe yield in order to meet their expected return. The U.S. financial system meet this rise in demand by transforming risky assets into safe, AAA-rated assets.

The Fed's low interest rate policies also increased the demand for safe assets for hedge fund managers. For them the promise of low short-term interest rates for a "considerable period" screamed opportunity. As Diego Espinosa shows in a forthcoming paper, these investors saw a predictable spread between low funding costs created by the Fed and the return on higher yielding but safe assets. They too wanted more AAA-rated assets to invest in so that they could take advantage of this spread that would be around for a "considerable period." Here too, the U.S. financial system responds by transforming risky assets into safe assets.

(3) Why doesn't the GSG hypotheis fit the data after 2005? If the huge CA surpluses (which reflect the global saving glut) coming from the emerging economies did, in fact, lead to the lowering of long-term rates in the U.S. economy, which in turn fueled the housing boom, why did long-term rates stop falling in 2004 and start rising in 2005? As the figure below shows, the U.S. CA deficit as a percent of GDP (red line) falls through 2006 and remains large through early 2007. The 30-year mortgage rate, on the other hand, stabilizes in 2004 and starts increasing in 2005. How is it that the saving glut could fuel low rates in the early-to-mid 2000s but not thereafter?

(4) Was the U.S. economy really a slave to the emerging economies during the early-to-mid 2000s? The GSG hypothesis has an underlying theme of inevitability. The implicit message is that the U.S. was destined to be a profligate spender because of the huge CA surpluses in Asian and oil-exporting countries. Really? Why couldn't monetary or fiscal policy have tightened during this time? Were U.S. policymakers truly constrained by the whims of foreign savers? This inevitability theme seems strange now that these same countries are complaining about the uneven impact of QE2 and begging the Fed for mercy. So what is it: is the U.S. economic policy a slave to the emerging economies or are the emerging economies a slave to the U.S. policy?

I look forward to hearing Chairman Bernanke's response to these questions.

Update: The Taylor rule Gap equals the Taylor rule federal funds rate minus the actual federal funds rate. Thus, a positive value for the gap means actual federal funds rate is below Taylor rule value or monetary policy is easy. The Taylor rule uses a 2% inflation target, the CPI inflation rate, and the

Laubach-Williams output gap measure.