Many observers are now viewing the Fed's decision in December to raise interest rates as a "policy error". With volatility in financial markets, falling commodity prices, and a fourth quarter slowdown many believe the Fed got ahead of the recovery with the December interest rate hike. Some even are even calling it a "huge mistake"or a "historic rate hike mistake". One person even called it an "epic mistake".

I see things differently. The Fed did not make a mistake in December. It made a mistake all last year by talking up interest rate hikes and signalling a tightening of future monetary policy. Since markets are forward looking, this expectation got priced into the market and affected decision making. The Fed did this even though the economy was not back at full employment. The December rate hike was just a confirmation of these expectations.

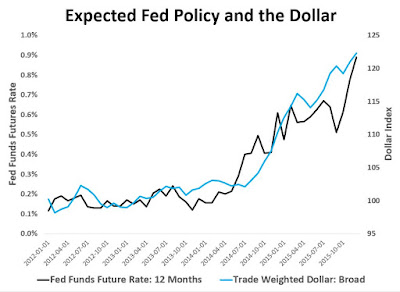

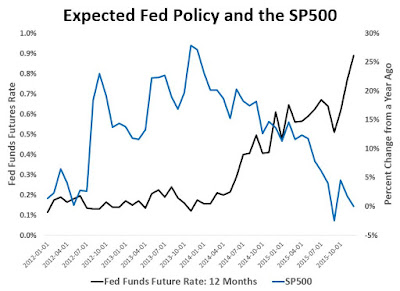

The Fed, in other words, got ahead of the recovery well before December. Damage was already being inflicted on the economy by the time the actual rate hike occurred, as seen in the figures below. They all show the 12-month ahead expected federal funds rate plotted against various economic indicators.

The first one shows the future federal funds rates alongside the trade weighted value of the dollar. Unsurprisingly, both start rising at about the same time in late 2014.

The trend growth of the stock market also began turning down about the same time as the expected tightening cycle began.

The expected tightening also coincided with a sustained decline in expected inflation as seen below. Yes, this is not a perfect measure of expected inflation. It has a risk premium in it that could be overstating the decline. But as Narayana Kocherlakota notes, if this is the case it only underscores the point that Fed has been overly tight. For a rise in the risk premium means an increase in the demand for safe assets and a decrease in aggregate demand growth.

The next figure show that the risk premium--as measured by the spread between BAA yield and 10-year treasury yield--did in fact coincide with the expected tightening signaled by the Fed.

The slowdown in industrial production that began last year also roughly tracks the expected tightening by the Fed as seen below.

Other indicators like the GDP in the fourth quarter, retail sales, or personal consumption also show a softening. In general, the point is that the Fed appears to have gotten ahead of the recovery well before December simply by talking up a rate hike.

Though the focus of this post is on the domestic U.S. economy, it is worth briefly noting the international implications too. As shown above, the dollar rose in step with the expected tightening of Fed policy. The stronger dollar, in turn, has pulled up the Yuan with it and this can explain why problems in China first emerged last August. China is dealing with deep structural problems and is doing so by violating the macroeconomic trilemma. That is, China is pegging its currency to the dollar, is easing domestic monetary policy, and is allowing some capital flows in an attempt to stabilize its economy. This is an unsustainable policy mix and is already creating financial market volatility.

Though it takes two to tango, the dollar surge over the past year helped push China into this predicament. China is now bleeding foreign reserves faster than ever and the timing of it can ultimately be traced backed to the expected tightening of Fed policy.

So no, the Fed did not make a mistake at its December meeting. It made a mistake over the entire past year and now we are seeing the fruition of this error.

Great post.

ReplyDeleteExcellent

ReplyDeleteThey bias what they expect with what they want

And end up conflicting with data dependency

"...the economy was not back at full employment."

ReplyDelete"The Fed, in other words, got ahead of the recovery..."

Two questions:

1. What's your measure of full employment?

2. What's your policy rule? Seems like anything short of "full employment" means you stay at zero.

My guesses

Delete1) Headline unemployment under 5%, U6 under 7%, with participation rate above 65%

2) Easiest policy rule ever: raise rates only when several (at least 2 third) inflation indicators are well above the target(2.3% or more) for several months in a row (or the running average on 6 months is above target for 2/3 of those inflation indicators), always erring on the safe side, which now means against deflation risks (30 years ago it meant against inflation risks). Inflation indicators: Core chained PCE, Core CPI, headline CPI, PPI, GDP deflactor, 5y forward, TIPS-implied inflation.

Which in the current world can translate as "unless you are almost certain that inflation is spiking comfortably over 2% for at least 6 months in a row never even think about raising rates".

Raising rates is like taking antibiotics, it works, but you only do it when absolutely necessary.

Where is the inflation you promised from increased policy rates?

DeleteGiven (1) and (2), that's a permazero or perma-subzero policy. Which is OK, if that's what you want.

Delete"Where is the inflation you promised from increased policy rates?"

1. 1/4% doesn't buy you much inflation.

2. You understand we only have December price numbers, I hope. The rate increase happened Dec. 17.

Great post. I have been doing sort of the same analysis and reach same conclusion.

ReplyDeleteYou can throw the oil price in the mix as well. Although Fed and other central banks take it as exogenous, the decline in the oil price coincides with Fed, PBOC tightening since July 2014, which to me suggests that it is Fed policy, and OPEC/Shale oil, that had caused oil prices to drop.

I think the PBOC is trying to avoid a similar to this over-communication error that the Federal Reserve committed--which would have harmed its credibility had it not hiked in December: https://ipehub.wordpress.com/2015/12/21/peoples-bank-of-china-again-not-following-the-fed-3/

ReplyDeleteDavid, if you take NGDP growth as indicator of the stance of monetary policy, the result is the same, with NGDP growth shooting down after mid-2014 when the "rate hike talk" became pervasive!

ReplyDeletehttps://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2016/01/17/the-plunging-economy/

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThought-provoking post! Can you be a bit more explicit about the counterfactual? Are you suggesting that if the FOMC consisted of 12 Paul Krugman types, all sending consistent signals throughout 2015 that rates would remain at zero thru at least 2016, that the S&P 500, US industrial production and Chinese reserves would not have declined? Is that what you're advocating? I get it that inflation expectations would have remained steady or risen (a good thing in recovery phase), but I'm not (yet) convinced that all of those other indicators were driven by Fed chatter. Can you explain the link to industrial production, for example?

ReplyDeletewhen will the FED and the Keysians admit defeat on the lowering of interest rates as stimulating inflation? they just bray for more.

ReplyDeleteThe FED will extend their mistake out into perpetuity.

ReplyDeleteDavid,

ReplyDeleteThe S&P500 tends to exhibit a stable, recognizable "trend growth" over a short time span? If you can support that thesis, I suggest you have billions to make as a quant!

The true counterfactual is to look at every other rate hike signalling period and see what happened to the stock market. Up until Jan, I suggest this one was an outlier in terms of how well the market stood up.

Excellent post; this is a better way of describing what happened.

ReplyDelete