Peter Stella joined me on the podcast this week. He was back by popular demand and we touched on two important and related questions: how should the government finance its relief efforts and who should ultimately manage the public debt? The U.S. Treasury may seem like the obvious answer to both questions, but it is not the whole story. The Federal Reserve can also finance the relief efforts and, in so doing, affect the structure of public debt. But is this a good thing?

Peter Stella says no, at least in the longrun. He makes the case that it is economically and politically cheaper to return the financing and management of the public debt back to the U.S. Treasury once the COVID-19 recession is over. In other words, the Fed's expansion of its balance sheet, an understandable response to the crisis, needs to be unwound as the economy improves. Otherwise, we might end up with two government agencies with very different objectives trying to manage the public debt.

This is an interesting argument and one I want to flesh out in this post by taking a closer look at the two questions of financing the budget deficits and managing the public debt.

Financing the Budget Deficits

The first issue is financing the budget deficit. The question here is whether the government should fund the deficit through (1) overnight debt with a variable interest rate or (2) long-term debt with a fixed interest rate. The former option is what happens when Federal Reserve liabilities--the monetary base--finance the deficit, while the latter option arises when it is funded by treasury securities.

The Fed financing of deficits, in other words, is not risk free. It could lead to higher financing costs as the economy recovers. In such a scenario, financing with long-term treasury securities with fixed interest rates would be ultimately cheaper. But is this even possible in the current crisis with the Fed buying up so much public debt? That is, even if Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin issued more long-term treasury bonds, the Fed's asset purchases have been so large they would effectively convert most of the long-term bonds into overnight reserves.

|

That, in fact, is what has happened over the past three months. The chart above shows that for March, April, and May, the Fed purchased about $1.67 trillion of treasury securities compared to $2.31 in new issuance. The Fed, in other words, bought up about 72 percent of the treasury securities supplied during this time.

Not only was the Fed buying up most of the new issuance, but it was buying up treasury securities with a maturity far longer than overnight reserves. This can be seen in the chart below. The Fed, then, has been acting as the final financier for most of the deficit during the COVID-19 crisis and, in so doing, has transformed the structure of $1.67 trillion of U.S. public debt into overnight government liabilities.

Managing the Public Debt

So are we stuck with these short-term government liabilities forever? As Peter Stella explained in the show, the answer is no. The U.S. government could convert those overnight reserves back into longer-term treasury securities once the crisis is over.

To illustrate how, imagine that by the end of 2020 the Fed has bought up $2 trillion in treasury securities. The purchase of these treasuries were used to indirectly fund the cash transfers to households, the PPP program, extended unemployment benefits, and other economic relief efforts. The figure below shows this development in terms of the respective balance sheets of the Treasury and Fed. The treasury securities are liabilities for the U.S. Treasury and assets for the Fed and vice-versa for Fed-issued reserves. The Treasury takes the reserves on its balance sheet and sends them to the private sector as part of the economic relief efforts.

If we now combine the Treasury and Fed balance sheets into a consolidated government account and also look at the private sector balance sheet, we see the following two t-accounts:

The net government liabilities are now $2 trillion in overnight reserves which are assets on the private sector's balance sheet. Again, during a crisis this is not a surprising outcome as the Fed rapidly expands its balance sheet. But left unchanged, it would imply rising interest rate costs once the economy starts recovering and the Fed is forced to raised the IOER to keep inflation in check.

To avoid this problem, Peter Stella recommends that after the crisis the Treasury issues additional long-term treasury bonds that lock in low interest rates. Selling these treasuries to the private sector means taking reserves off their balance sheets. The Treasury, in other words, is swapping long-term treasury securities for the overnight Fed liabilities. This is what the consolidated balance sheet would like after this activity:

Peter Stella outlines this process more thoroughly in his paper titled "Exiting Well". Again, this would not happen right away, but after the crisis has ended.

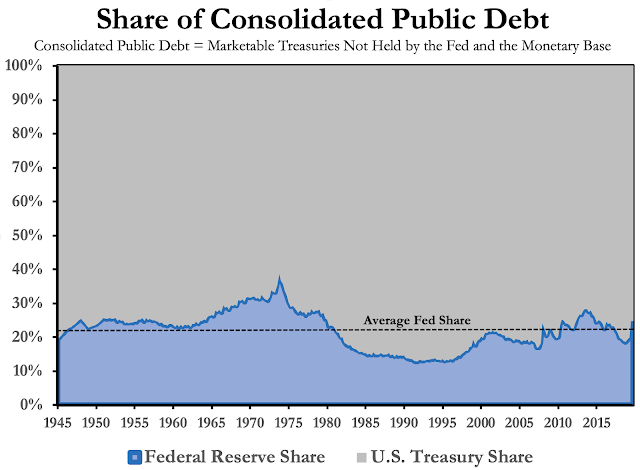

Historically, the Fed has financed about 20 percent of the consolidated public debt (CPD) based on data back through 1945. I define CPD as the sum of marketable treasury securities not held by the Fed and the monetary base. Using data from the Financial Accounts of the United States, I constructed the chart below that shows the share of CPD attributable to the Fed and the U.S. Treasury.

Unsurprisingly, the Fed's share of CPD during the Great Inflation rose to an average of almost 30 percent and hit almost 40 percent in 1974. During the Great Moderation it fell to about 14 percent. As of May, the Fed's share of CPD is approximately 24 percent, just above the historical average. The reason it is not higher is because of large budget deficits coming into the crisis.

If 'exiting well' means returning to the historical average, it might occur naturally with regular budget deficits after the crisis. If 'exiting well' means returning to something closer to the Great Moderation levels, then this will be a more ambitious project and require a vast reduction in the stock of reserves.

Other Considerations

The argument so far for reducing the Fed's management of the public debt is that it is likely to be economically cheaper. As noted by folks like George Selgin, Charles Plosser, Paul Tucker, and others, a second argument is that it is also politically cheaper for the Fed to avoid playing the role of public debt manager. The management of U.S. public debt is normally under the purview of the U.S. Treasury because this process is inherently politically and therefore overseen by representatives of the taxpayers. The Fed can avoid these political entanglements by minimizing its influence on public debt management. This, of course, requires a smaller Fed balance sheet.

A post-crisis journey to a smaller balance sheet, however, faces two big roadblocks. First, the Fed has chosen an 'ample reserve' or floor operating system. This keeps the stock of excess reserves large in normal times and therefore keeps elevated the Fed's influence over public debt management. A number of post-2008 bank regulations also has increased the demand for bank reserves. Some of these regulations have been tweaked in the crisis, but both they and the Fed's floor system would have to be reconsidered if we wanted to return to a world of scarce reserves and less political entanglement for the Fed.

Finally, it is worth noting that maintaining large central bank balance sheets do not guarantee robust growth. The charts below show the 2009-2019 averages of central bank balance sheets sizes against several measures of nominal economic activity. They, ironically, show bigger balance sheets are tied to slower nominal growth. Now, it could be the case that the countries with the weakest nominal growth responded with the most aggressive use of the LSAP programs. This is probably true, but the data span an entire decade so one would expect to see inflation, domestic demand, and credit growth respond to the use of LSAPs over this long of a period if QE worked as advertised. If nothing else, these figures should give us pause in considering the benefits of maintaining large central bank balance sheets over long periods. Further analysis of this data supports this interpretation.

So between the higher financing cost for the public debt, the greater political entanglement for the Fed, and the unclear benefits from maintaining a large central bank balance sheet over a long period, we should take seriously Peter Stella's suggestions for 'exiting well' once the crisis is over. Here's hoping we do.

No comments:

Post a Comment